I had a professor in seminary years ago say, “If you don’t understand the biblical call to hospitality, you don’t understand the gospel.”

That struck me as a radical statement at the time. What on earth does the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus have to do with welcoming strangers?

Everything, as it turns out. For that is precisely what God has done with us in Christ—welcoming us as the “strangers” we were in order to make us the “sons and daughters” that we are. In the gospel, God opens up Godself and makes room for us. And so we are saved.

Which is why the call to hospitality is so crucial as an ethical directive for the people of God—it is one of the principal ways that we make manifest the core dynamic of salvation, indicating both who we are and also what we believe about God and the good world he has made. Hospitality is how we “gospel.”

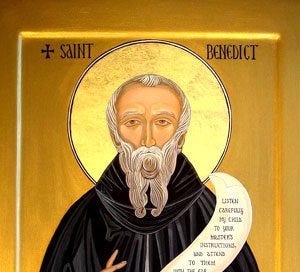

Benedict likewise shares that conviction. And it is deeply held. From chapter 53: “All guests who present themselves are to be welcomed as Christ, for he himself will say: I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (p. 51). The monastery is to be a place where the sacramental reality of “the other” is recognized and celebrated. And this according to the Lord’s own words. “I was a stranger and you welcomed me in”, Benedict reminds us, quoting Jesus’ famous teaching at the end of Matthew 25.

When we welcome the outsider into our midst, according to Benedict, according to Jesus, we are not just “being nice.” We are honoring and receiving the very presence of God.

So deeply does Benedict believe this to be the case that when a guest does in fact come to the monastery, there is nothing casual or haphazard about the way in which they are received. Quite the opposite, in fact—the entire community is to summon itself to welcome “Christ in disguise” (my phrase). He writes: “Once a guest has been announced, the superior and the brothers are to meet him with all the courtesy of love…Christ is to be adored [in them] because he is indeed welcomed in them” (p. 51).

This spirit of warm-heartedness pervades the Rule. Whether the visitor is merely a passerby or a priest, whether they share the faith or not, whether they are a traveling monk or one seeking to join the monastery, the community is to behave towards them the same: as embodiments of Christ, to be received as such. Again, according to the gospel of the Lord himself.

Now all of that is worth a good, long ponder. Are the boundaries of our lives porous enough to receive outsiders? I use the word “lives” instead of “homes” by the way, because I think that reducing this to a question of “How many new people have I had over for dinner in the last month?” is too small. Yes, important—by and large I think Christians should be pretty good at hosting dinner parties that draw new folks into our relational orbit.

But there are other ways to do this, too. Taking a coworker to lunch or coffee, for instance. Or lingering just a little longer over conversation with a neighbor on the sidewalk or in your backyard. Or heck—just putting yourself in a position where those conversations might happen. I spend a ton of time, for example, on my front and back porches reading and writing, and I’m always astonished at the kinds of conversations that take place just because I’m there and not tucked away in my study. Little conversations with neighbors that strengthen relational bonds—and also create opportunities to serve. “Hey, we’re going out of town next week. Could you take out our trash?” Absolutely.

These are the kinds of things that create space for the Spirit to work, the hospitable God acting through hospitality. Imagine that.

But what I find really fascinating in Benedict is his insistence that amid all this hospitality, the integrity of the community is never sacrificed. Yes, yes—receive your guests as Christ. And yet, when you do, “The divine law [will be] read to the guest for his instruction” (p. 51). There are rules here, bub. And while the abbot may break his fast to show welcome to the guest, the brothers, on the other hand “observe the usual fast.” The norms and rhythms of the community remain intact.

Even in cases where, for example, a visiting monk or a priest should drop in, the community must be vigilant in maintaining its integrity. Visiting priests often make bad guests—prone to presume too much and often standing in judgment upon the spiritual life of the brethren. Benedict warns a cautious hospitality towards them. “If an ordained priest asks to be received into the community, do not agree too quickly” (p. 58), he says. If the priest persists, he may be received, but “he will have to observe the full discipline of the rule without any mitigation.” Same for visiting monks: “Provided that he is content with the life as he finds it, and does not make excessive demands…but is simply content with what he finds, he should be received” (p. 59). If such is not the case, “he should politely be told to depart, lest his wretched ways contaminate others.” And as for someone wishing to enter the monastery permanently, Benedict prescribes a rigorous, year-long process of discernment. We will not give away what is most precious to us in the name of hospitality. The integrity of our common life matters.

This strikes me as deeply sane—its wisdom broadly applicable. How can I relate to anything, anyone, without a solid sense of “self”? If I lose myself in the process of entering into relationship with you, we do not, in fact, have a relationship at all. One party has simply been assumed by the other. I’ve been annihilated. I must be “I” and you must be “you” in order for the relationship to transact. Of course all relationships will “modify” the parties in them (Benedict recognizes this, too—as always, he’s intensely realistic), but if the modification is too great, the result is a kind of death.

Few modern writers have written better or more insightfully on this dynamic than the late rabbi and organizational guru Edwin Friedman. In his posthumously published book A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, Friedman contends that the capacity to distinguish “self” from “non-self” is the very essence of health—whether we are talking molecular biology, individual persons, families, churches, synagogues, or multinational corporations. In fact, he calls that “self-differentiating” capacity an “immune system.” If it fails, or turns in on itself, the entity fails.

By contrast, the stronger and better adapted it is, the more capable it will be of interacting meaningfully with whatever “others” it encounters.

The truth of this is not hard to see, is it? The most hospitable people I’ve been around have been simultaneously the healthiest ones—folks anchored in the right kinds of values, living them well, balanced and harmonious, with a robust sense of self. (Which, by the way, is exactly the thing Benedict has been trying to teach us.) Likewise the best families, the best churches, the best organizations… the best (dare I say it?) countries…

Actually, on that, let’s just say this, in the name of trying to add some wisdom to a conversation that desperately needs it. It seems to me that a Christian ethic of hospitality might usefully be deployed here. The call to hospitality is fundamental. But likewise is the call to maintain “bodily integrity.” Do a search sometime on words like “alien” and “foreigner” in the OT and see what you come up with. It’s instructive. Israel is to create space for “others”—precisely because they were once aliens and foreigners who depended on the kindness of God and others. But they also are called to remain “Israel”—or else what good are they? A spirit both of welcome and a commitment to good order, balanced in just the right way, is what makes Israel’s hospitality to outsiders possible. So also with us, and if we’re not fighting for that, I think we’re not acting wisely, or humanly, and probably setting ourselves up for disaster.

And all of this, of course, is grounded in God. For all of this is exactly what God does with us. He welcomes us into the society of Father-Spirit-Son and provides us with all the benefits of his God-ness… while forever remaining all that he is.

There’s your pattern.

Peace, friends.

A

Hospitality with a caveat: We welcome you to join our community, not change ours to suit you. The only caution is when welcoming a priest. How curiously ironic.

Thanks, Andrew. Hospitality is indeed a revolutionary act and an indispensable embodiment of the gospel. I appreciate what you've written here.