(Note: The following is the ninth installment in a series of posts on The Rule of St. Benedict and what it might have to say to us today. You can find the first one HERE. Also, as we do this, you might find it helpful to follow along in your own copy of The Rule, which is probably available as a pdf online, and definitely available in hard copy. I bought and have enjoyed THIS ONE.)

“The way up and the way down are one and the same way.”

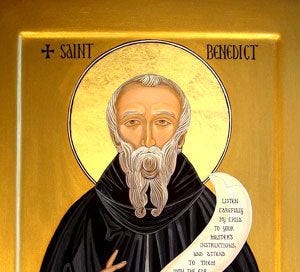

So said the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, and had Benedict been aware of Heraclitus’ words (perhaps he was; we don’t know) he may well have used them as a kind of credo for the way of life he was advocating—a life of upward ascent to God that is paradoxically rooted in the downward way of humility (chapter 7 of The Rule).

Benedict spies the paradox everywhere in Scripture—captured with crystal clarity in the dominical utterance, “Everyone who exalts himself shall be humbled, and he who humbles himself shall be exalted" (Luke 14:11). Benedict explains:

“In saying this [he] shows us that all exaltation is a kind of pride…Hence, brethren, if we wish to reach the very highest point of humility and to arrive speedily at that heavenly exaltation to which ascent is made through the humility of this present life, we must by our ascending actions erect the ladder Jacob saw in his dream, on which Angels appeared to him descending and ascending. By that descent and ascent we must surely understand nothing else than this, that we descend by self-exaltation and ascend by humility. And the ladder thus set up is our life in the world, which the Lord raises up to heaven if our heart is humbled. For we call our body and soul the sides of the ladder, and into these sides our divine vocation has inserted the different steps of humility and discipline we must climb.”

From there he’ll give us his famous “12 Steps of Humility”, which are as follows:

Always keep the fear of God before your eyes

Abandon self-will

Submit to your superiors

Endure everything, especially contradiction, without seeking escape

Confess your thoughts, especially your sinful ones

Be willing to accept menial work

Regard yourself as less than everyone

Only act according to the rule of the monastery

Restrain your speech

Refrain from “ready laughter”

Speak gently, seriously, modestly, and reasonably

Demonstrate humility not only in heart but in your entire demeanor (nothing ostentatious)

These things are difficult, no doubt. The upshot of practicing them, however, is that, according to Benedict, over time they will not only become easier, but even delightful. We’ll have entered into the joy of a life perfected in the humble love of God:

“Having climbed all these steps of humility, therefore, the monk will presently come to that perfect love of God which casts out fear. And all those precepts which formerly he had not observed without fear, he will now begin to keep by reason of that love, without any effort, as though naturally and by habit. No longer will his motive be the fear of hell, but rather the love of Christ, good habit and delight in the virtues which the Lord will deign to show forth by the Holy Spirit in His servant now cleansed from vice and sin.”

Now without commenting on each of the steps—or even, frankly, endorsing them in all their detail (let’s be honest, I’m not interested in living in a community where we refrain from “ready laughter”; and likewise, “regard yourself as less than everyone” might be, however well-intended, more harmful in the long run than helpful) let me just tell you a few things that I really appreciate about Benedict’s vision here:

First, it roots the call to “ascend” to God firmly in the dirt, in the soil and substance of life together. The Word became flesh, after all, and made a dwelling with us. The motion of the divine life has always been towards this world, and not away from it. Likewise, the directionality of any spirituality that can be rightly called “Christian” is towards the very heart of the world, not away from it. An authentic Christian spirituality is always and forever rooted in and attentive to what Eugene Peterson often called “conditions.” We ascend to God in the details of our lives, and not away from them.

Unfortunately, across the centuries of Christian reflection, we have often not spoken of this rightly. I am thinking of the countless books I have read that talk about spirituality—the “ascent” to God—as though it were gnostic flight from materiality, a private vision of the divine essence, an escape from “conditions.”

Benedict, for one, won’t let us go there. If we want to find God, we will find him in our lives. There, and nowhere else—in a world of spouses and children, bosses and coworkers, neighbors and friends, all of whom have various claims on us. Likewise, we find him in a world of bills and chores and mundane tasks, mowing the lawn and taking out trash—duties that must be tended to in order to keep our lives spinning, duties that are ours and no one else’s. It is along the path of relationship and responsibility that we ascend the hill of the Lord.

Which gets to the second thing I really appreciate about Benedict’s vision…

It gives us a helpful framework for thinking about what we might call the “psychology of humility.” There is a very great part of the Christian tradition that approaches the psychology of humility through the lens of “self-abasement” – basically, thinking of yourself as garbage. Much as I appreciate, for instance, Thomas á Kempis famous Imitation of Christ, it can at times come off as self-flagellating to the point of brutality. Many of Benedict’s lines, to be honest, betray just that same sentiment (especially steps six and seven, and other things scattered here and there throughout his work).

Yet what I spy in Benedict’s overall vision of the humble life is not really self-abasement but rather a kind of delighted self-forgetfulness. Benedict wants us to lose ourselves for Jesus in our lives—again, in the very conditions in which we find ourselves. He wants us buried like seeds in the soil of relationship and responsibility.

That, after all, is the essence of humility, even on the linguistic level. Like the word from which it derives (humus—“earth”), the humble life in the final analysis is a fundamentally “earthed” life, a life “grounded” in community, in a network of relationships and responsibilities that constitute our path to God. No one pursues humility in a vacuum. We do it with others, in the context of family and work and church and all of that. Our lives—these very lives—are the yoke that our good and humble Jesus has given us. We are not to stand above them in judgment but to be in them as glad participants, sharing the joys and burdens of a common life together.

Which gets to the last thing…

We do all of this with a happily and freely submitted spirit, keeping a keen eye out for the sense of entitlement that so often creeps in and ruins our common life. Notice again that line—“all exaltation is a form of pride.” That’s worth a ponder…

Over the last few years I’ve sat with a number of folks—believers—who were contemplating leaving their marriages. When we talked it out, it wasn’t abuse or infidelity that was driving them away from their spouses. It was, instead, a vague atmosphere of dissatisfaction with the way things had turned out. Deep down, they thought that not only could they do better; more, and far worse—they thought they deserved better.

That’s pride, folks. Exalting yourself above your life.

I would sit there and plead with them: “Don’t do this. Don’t leave. Yes, your life can be better. But not by blowing it up. Not by destroying the framework. Not by abandoning your people. You need to stay put. Do the work. Have the hard conversations. Face your fears and insecurities. Stare down your demons. There’s fruitfulness in your life if you’ll have the courage to stay inside it.”

Almost always they chose otherwise.

The grief and pain are indescribable.

Pride set the stage.

And that’s what Benedict knows. The only way any kind of community can survive is along the narrow road of humility—practiced daily by each of its members as we fight to “stay put” with each other (see #4 of the 12 steps). Which, after all, is precisely what the New Testament teaches:

“Be completely humble and gentle; be patient, bearing with one another in love. Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace…” (Eph. 4:2-3)

By the humility of the Son of God the world is saved.

By the humility of the people of God it is preserved.

So difficult to watch marriages struggle and fall apart when a spouse chooses to drink the Kool Aid claiming there’s something better “out there”. As I’m peeking over the horizon to next year’s Golden Anniversary, I can honestly say that we would have missed the richest season in our marriage if we’d split any time something that seemed better drew us off course. Sure, we’ve fought, screamed, walked off, slammed doors. I’ve even left for a short while, staying with my brother until I could get my head cleared. We sought counseling when we were at a stalemate. But somehow, after our nest emptied, all the annoyances of earlier marriage no longer felt so annoying. In fact, we’re mostly amused at the very same things that previously drove us crazy.

And now we’re planning that long awaited 50th wedding anniversary trip to Costa Rica. The sons and their families will join us. We’ll ride ATVs, Zipline and rappel, hike, swim and snorkel. At days end, we’ll all share memories and celebrate a very good life. To God be the glory!

It would seem, I keep falling off the ladder!🪜